Cono Tripi

Vessel Name: Sydney

Cono Tripi

Drowned at Sea;

Body recovered and buried at Fremantle Cemetery

9 October 1913

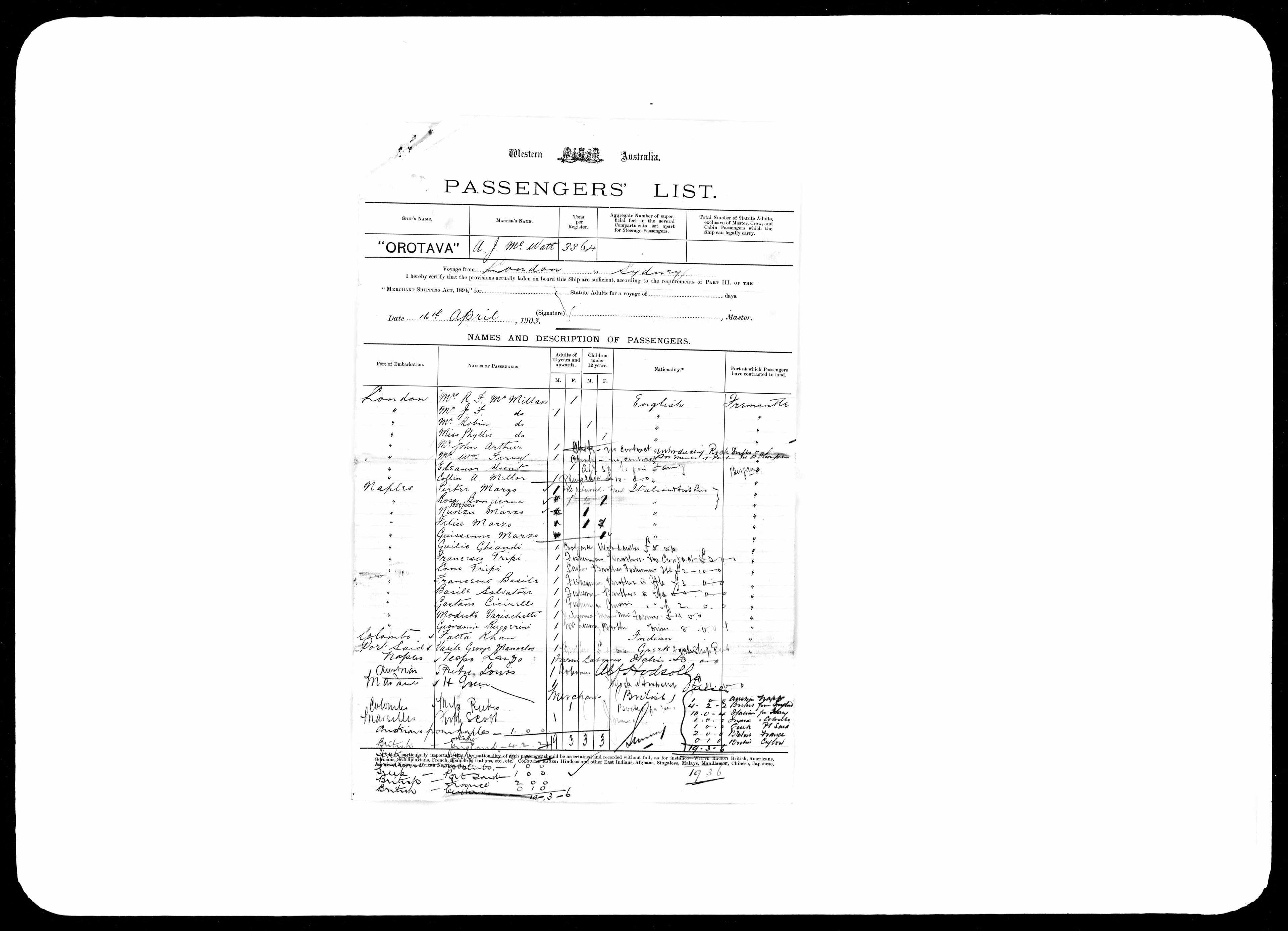

Orotava's passenger list shows Cono Tripi arrived on the ship

Cono Tripi was likely born in Capo D’Orlando in Sicily, around 1885. He arrived in Australia with his brother Francesco, onboard the Orotava in 1903. They were part of the travelling party that included brothers Francesco and Salvatore Basile, as well as Gaetano Cicirello, all prominent names in the early WA fishing fraternity.

In 1910, the two brothers operated the fishing vessel Sydney and the West Australian newspaper sent a reporter to spend the day with them onboard their vessel, as they pulled their craypots. It is one of the earliest detailed accounts of commercial crayfishing near Rottnest Island.

On 9 October 1913, Cono Tripi and a fellow fisherman went fishing, likely leaving from the Rockingham area. There were reportedly heavy rain squalls at the time, and the boat capsized near Penguin Island.

There are mixed reports in the newspapers, some claiming Cono was a strong swimmer, and others stating the opposite. Cono’s mate successfully made it to shore and survived, but Cono was drowned. His body was recovered some eight days later on the 17 October, and he was buried the next day in Fremantle Cemetery.

The West Australian

Tuesday 18 January 1910

Page 5

“FRESH FISH.” WITH THE FISHERMEN. AMONG THE CRAY-POTS.

(By S.R.)

Come winter, come summer, it is all one to the fishermen, mostly Italians, who form a community in themselves at the Port. There are fish in the sea to be caught, and crayfish to be enticed from their haunts, among the reefs and hauled to the surface, so with seaworthy little craft at their command what matters it to the fisherman if the wind be cold and the waves icy or in season, the sun scorching?

Twice a day the auction sales attract buyers to the Municipal Fish Markets, and stocks must be provided daily. So out go these hardy toilers of the sea to win from the waters of the Indian Ocean their living treasures.

When all the boats are in and on the tables of the markets are displayed the fruits of their labours - all save the crayfish, which are not put through the market - what a merry, laughing crowd it is!

Among all the Italians there is hardly a sour-faced visage. As a boat arrives, drops her anchor, and backs into position near the landing place, merry greetings pass between shore and boat.

The rapid flow of the Italian's language is heard on all sides; everyone seems to be included in the conversation and queries, answers, greetings, conversation intermingle so that even if one understood their speech it must prove bewildering. And when the newcomers step ashore they are enthusiastically hugged and kissed by some of their friends, a proceeding which, while strange to the matter of fact Australian, is after all only a natural emotionalism on the part of the Italians.

The fishermen at Fremantle - and these supply the bulk of the trade of the State - may be divided into two sections, namely, those who deal in crayfish only and those who deal with fish in the ordinary sense of the word. The latter have to put their "catches" through the markets to be submitted to an examination from a health standpoint, and in due course sold. The former, however, make no use of the markets.

At the inception of the present regime, efforts were made to bring crayfish under the operation of the market authorities, but experience showed that such a course could not profitably be continued. Now the hauls are spread out on the wharf to satisfy the fisheries inspector that the “crays” are of the regulation size, and then they are packed into baskets “all alive O,” and sent up the line to fulfil orders as far inland as Kalgoorlie and Cue, or to the ocean-going liners which call at the Port, there to be served up as delicacies to the passengers at (say) Colombo.

Of course, large numbers of the crustaceans find their way into the shops in Perth, the proprietors of which in some instances part-own the boats from which they draw their supplies. When, however the demand does not exhaust the boat's contents her surplus stock Is liberated into large crates, which are kept under the fish markets jetty, and when trade brightens again these are absorbed as well as the fresh supplies brought in daily by the “cray” boats.

“It seems a cruel thing to do,” remarked a well-known fishing expert recently, “but the only safe way to cook crayfish for eating is to drop them into the pot alive. Yes, it is cruel, but when the public health is taken into consideration it is perhaps to be condoned. If crays are alive they are good; once dead they go bad very quickly, and then woe betide him who eats of the dish!"

It is estimated that some 6,000 dozen crayfish are taken from the floor of the sea and consumed annually, and yet few people comparatively speaking - know how the supplies are garnered by the Italians. With a view to gaining first-hand information on the subject, I managed one morning during the week to board a fishing craft bound for the grounds.'

The boat - the finest and cleanest in the cray' fleet - might have been a pleasure craft were it not for its business like- appointments, fishing lines, spare sheets and sails, half a dozen bullock's heads supplied by the butcher (after everything useful to him has been stripped off the bones) for bait - all stowed neatly away, and the boat itself spic and span as though it had been newly hosed down.

A staunch craft, some 30ft. long, with a beam. of about 10ft. drawing 3ft. 8in., and well ballasted. Decked on for'rad well aft of the tall mast, she has a hatch which, extending well amidships, gives ample cabin space for the crew of two - Frank (the skipper) and Cono, his assistant.

Amidships is the well, kept constantly replenished with clean water, which finds entry through holes bored through the hull. Extending about 5ft. in length, with' a breadth of about 3ft. and ' depth of a couple of feet, she can carry hundreds of the crustaceans in the well.

Then aft is a roomy space, from the hatch to the stern, from which the boat is handled, and into which the crays' are tumbled when the grounds are reached.

Painted a useful slatey-grey, which is well-washed daily, the boat named the Sydney, is a source of pride to her owners. And the men themselves, spruce, cheaply-clad, cleanly, soft eyed Italians.

A stiff land breeze is blowing when we drop out 'round the farce, termed a "breakwater,'' which runs out from the markets jetty, and square away under the big peaky mainsail. Once well under way Cono, the assistant skipper, prepares the bait in readiness for use later on. Half a dozen bullocks' heads and a three-foot shark are cut up, into junks and some of the former - bait left over from a previous trip - smells abominably and is thrown overboard.

“Too bad,” explains Frank, as he stops for a moment in swabbing down the decking, “the crayfish won't touch it when it is like that. It's no good at all.”

Past the end of the Long Jetty, the Sydney bounds along surging over the choppy swells and leaving in her wake a white frothed way, for the craft is one of the cracks of the fishing fleet.

From the interior of the cabin the buzz of a Primus stove is almost drowned by the crackle of frying fish, and presently Cono - he acts as cook - emerges with hunks of bread, a plate of fried schnapper and “cray” done to a turn in oil, and a strong cup of tea.

“You like fish,” queries the skipper, with concern writ large on his face; "ah, 't's good.. It's all I get, but we do well on it. You people eat too much-a meat; no good ‘in this climate. Fish better. Go on-try”

So, as the boat, running dead before the wind, makes out across the Roads towards a gap in the reefs we three break our fast. On shore, even at that hour, the hot easterly wind must have been making for discomfort, but out in Gage Roads it blows cool and fragrant, and the seagulls flitting about seem to revel in the early morning freshness.

Away down in the northern horizon, the funnels of the inward-bound P. and O. liner slip along the sky-line and away astern, the Customs launch dances out to the German cargo boat anchored off the moles. A large wave surges up lifts the boat and moves past.

"Big seas today," remarks Frank, as he eases the boat a point or two and glance at the reefs, rapidly looming up ahead. The remains of the barque Ulidia wrecked on the Straggler Reef slip away to starboard and to port, the Straggler Rocks are passed.

The darker blue of the deep water has given way to the mottled surface of the shoals and a couple of fathoms below the dark masses of reef, with the pale sandy patches between, seem scarcely tolerant of the craft scudding above them. On and on the boat sails out across the Indian Ocean past the western point of Rottnest.

Both Frank and Cono don overalls. With thick aprons tied round their waists and thick brown slouch hats on. Suddenly Frank points out over the port bow and says ungrammatically, “That's them!”

“That's what?” I queried, for in the direction he indicated unpractised eyes saw nothing but an uninterrupted vista of heaven sun-kissed waves reflecting a glorious blue sky.

Cono laughed, but aided in the search for the mysterious something for which the skipper was flattening the staysail and mainsail a trifle and making up.

“See the corks,” Cono said, and there some 50 yards ahead stringing out on the long swell a line of corks is to be seen, the first - that is at the commencement of the line – having a spike directing it. When almost abreast of it the boat is put on the wind, and as the craft dashes past the corks, Cono leans over with a long wire-hook and secures the line, which is pulled aboard.

About three fathoms of line, with a lump of cork attached about every 10ft, lies at the bottom of the boat. The line comes easy over the trawl roller set on the gunwale. Together the two men pull hand over hand, dodging the water splashed by the occasional whirling corks which are tied to the line at intervals right down so as to aid it in floating properly.

Presently a dark round object with white patches showing ghostly appears at the end of the 30 fathoms of line out of the darkness of the denser waters, and is heaved aboard. It is the cray-pot. Strongly built of tough woods, set in strips about an inch apart on a staunch frame, it has a round floor 3ft. in diameter, the sides rising cone-shaped for a height of about a couple of feet, and in the roof an opening, with the sides sloping downwards and narrowing towards the bottom, is left.

Through the opening the crayfish are enticed into the interior of the pot to get at the bait, which is suspended inside the pot, and they “bein' more'n common stupid, can't find the hole to get out again.”

The white patches, which glowed so ghostly, are the bones or flesh which was put in for bait, but which has served its purpose, having been shorn of all their succulency, and, bloodless and tasteless, is now unfit for any decent crayfish. But they have done well, for in the bottom of the pot a dozen fine sized crays have been captured.

Cono, slipping a coarse glove over his right hand, quickly transfers the crays from the pot to the well in the boat. Meanwhile Frank has his boat moving again, this time in a southerly direction, for he has five pots laid down here. The same procedure is gone through, and the next pot contains eight crays and a fine, fat leatherjacket.

Only five of the crayfish are kept, however, for the others are undersize, and are tossed back into the sea. A spike is put through the leatherjacket's eyes, and he is strung up for bait. So to the next pot. Twelve “crays” are here; six are tossed into the well, six go overboard and the pot, freshly baited with sharks’ body and the jawbone of a cow, is stacked with the other two, when the remaining couple of pots are hauled aboard these are set in 20 fathoms of water.

Frank pushes on to another spot which he knows of, and, choosing the right place, cries out sharply to Cono, who sends a pot clattering over the side, and pays out the line to let it sink properly. When it has reached bottom and is snugly ensconced among the reefs some half-dozen corks are floating on the waves. At intervals of about a chain the other pots are put down.

Next the Sydney is piloted to another spot further out to sea but nearer to Rottnest, which is distant some two or three miles, and here more pots are hauled laboriously over the trawl-roller from 25 fathoms - hard work indeed and poorly repaid, for the percentage of "underweights" exceeds that of the marketable crays.

So the day passes, slipping from one place to another, coming with unfailing accuracy upon the various plants, the Italians discerning the floats from afar on the crest of the waves, then the dive after the line by Cono with his hook, and the pull, pull, pull to drag the pot from its resting place among the things that crawl over the floor of the sea; the emptying of the pot of its lively prisoners, the rebaiting and subsequent resetting in a fresh spot.

What a laden little craft she looks as she bobs along with half a dozen pots crammed aft on her deck. Well for the little Sydney that the skipper knows his work, for the vicious breakers on the outer reef off Rottnest fill the air with their roaring, and seem to clutch at the boat as he puts about and makes for safer waters.

In all, during the day 22 pots are hauled aboard and robbed of their contents from depths averaging about 20 fathoms. The day's haul works out at ten dozen - 120 crayfish, worth 5s. a dozen. An average haul, they say - and they are satisfied.

“That is the lot.” Cono looked satisfied, and Frank stretched himself as he leaned against the tiller and added, "Now we make for Fremantle, Not too much wind yet, we want more, and perhaps, it will freshen. These easterlies are no good. Much-a nuisance."

The wind which earlier gave promise of developing into a sea breeze, swings round to a dead easterly, and a long beat for home is the result. Buckets and swabs are brought out, and the Sydney being laid on her course, cleaning-up operations are commenced. Not until the boat is spic and span; her boards showing clean and her paintwork looking spotless, do the men think of any lunch, though it is well past 3 o'clock.

While the skipper puts the finishing touches, Cono repairs to his culinary department, and prepares the lunch -macaroni done in tomato sauce and oil, with dry bread. A huge dish full is prepared, and steaming hot, is set beside Frank at the tiller, Cono having himself annexed a big plateful of its contents.

Lazily the boat glides sluggishly along and a shark, making out to sea, ranges alongside, gazes at her white sides for a minute or two, and then disappears.

Under the spell of the surroundings the skipper becomes communicative. “What is a fair payment for our work?” he asks, and smiles at the suggestion that Cono is worth more than £3 a week. "No, we couldn't do it. We have 10 dozen on board now, which, at 5s a dozen represents £2 10s., half of which goes to my partner. Out of the 25s. which I get I have to keep my wife and home, and get tucker, and bait.

Yes, the returns are small, and' an Australian couldn't make it pay. We can, because it costs us so little to live. We work hard enough. Look at our hands. all hard and cut. 'And then the monotony of the work. Yesterday morning at sunrise, I was doing the same work as I was at sunrise this morning, and yesterday afternoon at this time we were just about where we are now.

Once every day we haul the pots, collect the crays, and as you saw today, have to throw about a third of them overboard because they're too small. That is the trouble off Garden Island. The crays there are too small, and wouldn't pay. At Rottnest they are better, but we lose a lot that we catch. In the summer the work is not bad, but in winter, when it is cold and wet-well, it is not living.

Sometimes we go out and don't get many. The pots often don't contain a single cray. It's bad for us then. At other times, when it is rough, we can't find our floats. The currents carry the lines with the corks down, and then we have nothing at all. Sometimes the lines float up after the currents ease up, and we get them again. At other times they never rise, and we lose our pots, lines, and corks - more than 30s. worth' That's hard luck eh? Oh! the shore people have the best end of the stick, eh, Cono? That's right."

After a long beat, the Long Jetty draws up on the port side, and, in the gathering gloom, Frank takes his craft round the breakwater, "douses" the sails; Cono pays out the anchor chain and the Sydney drops back to the land stage and is berthed for the night.

Tired from a long day's hard work, the two fishermen stroll quietly home. In the morning they will empty the well of its contents, and such as is not required for immediate consumption, will be stored in the large crates under the jetty. Then-up sail and out to the grounds again.

Such is the life of the men of the cray fleet, which number in all eight craft, only one of which fishes inside the reefs which surrounds Rottnest. The other tend their pots in the deeper waters ranging up to 30 fathoms, and among them they set 60 odd pots daily. From these they take vast numbers of crays, estimated to aggregate some 72,000 during the year.