Charles Goldsmith

Vessel Name: Islander

Charles Goldsmith

Lost in pursuit of a whale; body not recovered

12 August 1875

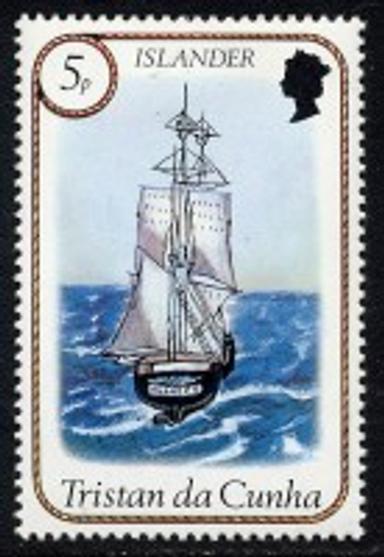

A postage stamp featuring Islander

The whaling barque Islander has a mysterious past. Records and ship’s logs prior to 1871 are sketchy. Some sources consider Islander was a British vessel built in Sussex in 1864, while others believe she was built in 1856 in Fairhaven, America. The British version has Islander trading general cargo between Australia and London until 1873. The American barque was thought to have made her first whaling voyage to the Pacific in 1856, continuing to hunt whale each year in the Pacific.

Islander was a three-masted barque weighing 200 tons. She was 92 feet long, 23 feet across her beam and she drew 12 feet of water.

In both scenarios Islander was sold in Albany to an Australian consortium of five merchants, one of whom was William J Gillan. She became one of vessels in the small but active shore-based fleet hunting from Hobart to Fremantle. Captain Hiram Ellis Swift was the mate onboard Islander before he assumed command in 1875.

Islander’s new owners, led by Thomas B Sherratt, ordered a complete re-fit in Princess Royal Harbour. In 1871 she had been copper-sheathed and had been classified “A1” for five years by Lloyds of London. The new refit included reinforcing the bow, adding a whale-slip and four new whaleboats with heavy duty davits to lower and regain them.

A new local crew was recruited. Included in her crew were William Gillam (part owner), John Consalvo, a Madeiran and Charles Goldsmith. They were long-term locals, and according to the newspapers, were well-known in the southwest coastal communities.

Captain Swift ordered new sails, five years of whaling gear and enough casks to hold 100 tons of oil. His new command manned four whaleboats, and he optimistically stocked up on gear to catch sperm whale. The cost of the refit was £4,500.

On 9 April 1872 Islander put to sea from Albany and sailed east past Esperance following whales. Off Cape Arid Captain Swift ordered two whaleboats over the side in a heavy sea to close on the whales.

Charles Goldsmith was a harpooner. He was one of several Goldsmiths littered throughout the southwestern whaling industry. Although Charles was 32 years old, he was single and had no children. Albany whalers spent between 12 and 18 months at sea at a time, and the southwest’s female population was limited.

Charles stood in the bow of one of the two whaleboats launched to attach to the whale off Cape Arid. A harpooner was the man in the bow who pulled the forward oar in the whaleboat, harpooned the whale and then steered the boat until the whale could be taken to the ship for processing. Where he stood in the bow there were harpoons, and their long ropes coiled at his feet.

Charles signed on to the Islander at Hobart for the 1872 season. The shore-based crews gathered in Albany when the whaling season was due to begin and signed on for a season with one of the ships gathered in the harbour.

On 12 August 1872 Charles was harpooning a whale in a heavy sea 30 miles southwest of Cape Arid. He had lanced the whale and was stood in the bow steering the boat which remained attached. He was known for his strength and a steady nerve. He steered the boat after the whale.

As the crew awaited the whale’s imminent death a large wave swamped their boat. Charles was standing with his harpoon. As the boat was swamped, he was thrown but remained on his feet. The harpoon rope played out as the whale continued to swim. It looped around Charle’s leg and as it tightened, playing out with the whale, it dragged Charles over the side of the boat and into the water. He was dragged under water attached to both the whale and the boat with no way to be free.

It did not take long before the ropes had played out to their full length and were stretched to capacity. Eventually they parted under the tension. There was no one in the boat’s bow to control the ropes, and the first rope soon parted and allowed Charles to surface. The second rope could not hold by itself, and it parted soon after the first.

The crew saw Charles struggling in the churning water, still clutching his harpoon. As he disappeared under the surface, they alerted the ship. Still attached to the running whale, the boat crew could do nothing to assist Charles.

The Islander turned and started a search for him but found no trace. When the ropes finally parted, the whale and Charles both sank. He was not seen again.

The ship’s log mentioned Charles was “lost overboard in pursuit of a whale”. His disappearance was noted in the local newspapers as a “sad reminder of the perils of our coastal trade”.

Charles’ death also prompted a call for better-equipped whaleboats and lifejackets for the crew. Charles is commemorated on the Able Seamen’s Memorial in Princess Royal Harbour.